Here is a recording of David reading the Yonder.

David Howard is a poet and the founding editor of literary magazine Takahe. He has also worked as a pyrotechnic and special effects supervisor for acts like Metallica and Janet Jackson. His poem The World of Letters was selected into one of the official UNESCO City of Literature Wall Dots.

Here is our conversation on how he started writing poem, how working with fireworks as a pyrotechnician affected his work, what it was like to start at age 40 and what he thinks of the wall dot design. We also recorded him reading one of his photography related poem Yonder.

ALEX: How did you start writing poem and, more importantly, why do you write poems?

DAVID: I decided that I wanted to be a poet after reading extensively in the Canterbury Public Library, and being particularly taken by a French poet, Arthur Rimbaud, when I was 12. I was also reading the English playwright, Christopher Marlowe, and they made a great impact on me. I was impressed by the violence of language. Violence looks much more attractive when I was 12, they were really exciting. Poetry, seemed to me, a romantic endeavor, an adventurous way of presenting oneself to the world.

I, going through adolescence, suffered all of the disasters that most of your readers would have suffered during their adolescence. I embarrassed myself with the opposite sex. I embarrassed myself with my friends. I made mistakes in terms of overestimating my ability, but the one constant was that I was always reading poetry, and I was always trying to write it. It gave me a kind of stability.

I make poems so that I can understand more clearly who I am, and what my place is in the world. It's an existential enterprise.

ALEX: What would people be surprised to learn about you?

DAVID: I trained as a pyrotechnician.

I had always been interested in fireworks, and I spent almost all of my 30's working full time as a pyrotechnician. That was really bad for my writing. I got almost no time to do any substantive writing, but it was very good for my perception of the role of language. I didn't produce very much. I didn't establish my career, despite a good start, in a way that some of contemporaries of the same age did.

I wound down my pyrotechnics career at the age of 40, realizing that if I didn't make a serious attempt at writing it wasn't going to happen. When I came back, I had an entirely different sense of what was possible in language. Because I had been choreographing against the sky, I approached the page as a kind of sky.

I started to look for concentrations of color on the page. Line by line, stanza by stanza, poem by poem. In that, it's got a similarity with fireworks.

Imagine the night sky, and a firework bursting, and then another firework bursts through it, so you get a ghosting effect. Then, there's what's called a willow effect which is a dropping effect so you burst something about and it drops through an effect.

Well, you can actually do that on the page with language, and I would never have thought of that, if it wasn't for my background.

ALEX: Tell us how do you achieve that effect?

DAVID: You need to view the page as something mobile, not as something fixed. You have to get as many time frames as possible on the page.

You treat time as if all times are simultaneous.

The history of each word that you load on has to be in the line to a greater or lesser degree. You don't actually write a poem. You choreograph a poem. It's a dance through time.

ALEX: What do you feel of this photograph? What did you have in mind when you wrote this particular poem?

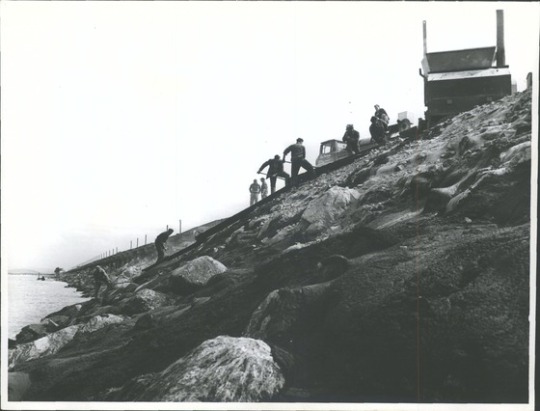

(Credit: This photo was taken by Dunedin Photographer David Steer. You can check out more of his work on 500px.)

(Credit: This photo was taken by Dunedin Photographer David Steer. You can check out more of his work on 500px.)

Here is a short behind-the-scene story from the Photographer David Steer.

I would certainly have liked to have photographed the mole in its heyday but this photo was taken on a chili evening at the end of May 2014.

My wife left me to it, heading back to the car after a walk with a warning not to fall in.

The ingredients for a decent photo are all there, it was just a case of being able to balance my tripod on a boulder for 20 second while the photo was captured without moving at all.

The seagull was a bonus as they normally move and end up looking ghostly transparent.

DAVID: This image of Aramoana mole worked very well with the poem, because they're both to do with mutability. The picture is to do with the mutability of human and settlement; and the poem is about that as well.

The mole is a device that actually stops the harbor from silting up. It was built to stop sand making the harbor too shallow to use for large ships, so it's been integral to the successful settlement, and maintains settlement and growth of Port Chalmers and Dunedin.

That area, immediately alongside the mole, is such an important part of the photograph. It is the wreck and it’s the remains of the railway line where the rocks were brought out to build the mole. There was a few of time frames there simultaneously.

There's an architecture in language that the photographer writes large in the image, and the structural elements in the picture resonate well with the idea of bone China, which is a kind of class loaded idea. Only the wealthy have bone China, but bone,

of course, is human, as well.